Sharper Perspectives: USB Microscopes for Enhanced Learning and Research (Video Included)

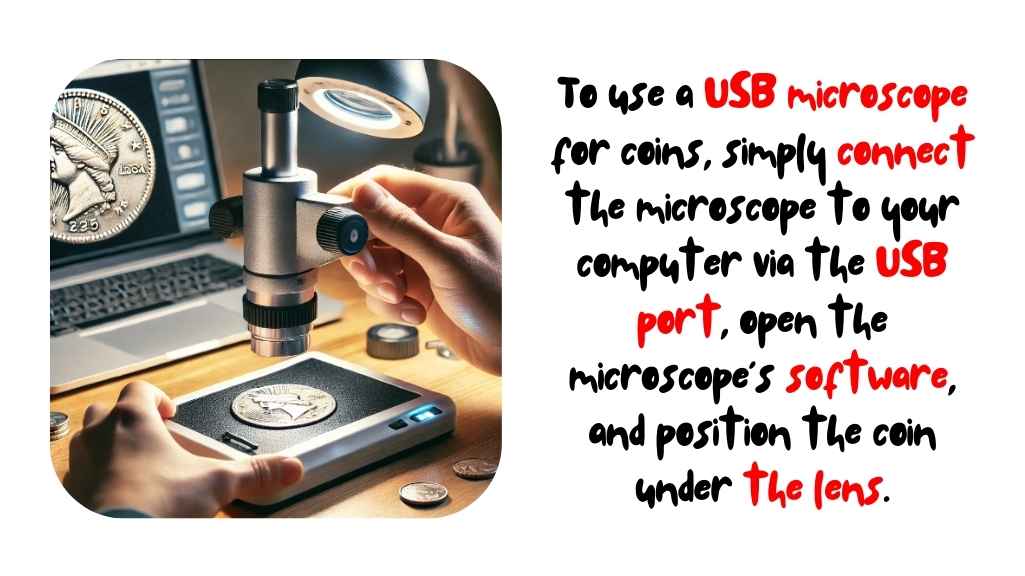

Having analyzed various customer reviews, technical specifications, and expert opinions, I am confident in providing you with a list of the 5 best microscopes with USB. Whether you’re an educator, scientist, or hobbyist, these microscopes will provide you with a clear and detailed view of the microscopic world and are compatible with your digital devices. […]